Although the movie’s conclusion implies that Travis is now more psychologically stable, Scorsese drops an artistic bomb in the final few frames.

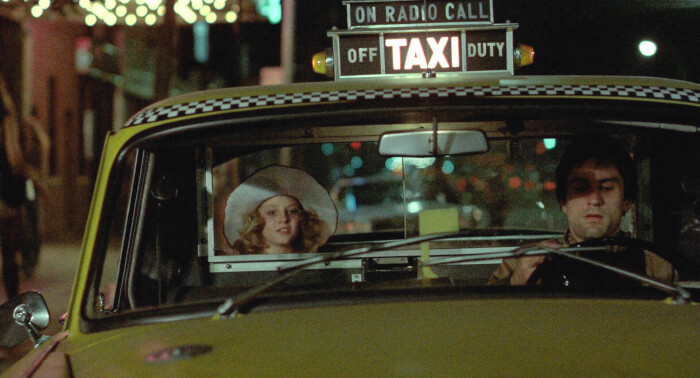

Martin Scorsese’s 1976 film Taxi Driver, starring Robert De Niro as Travis Bickle, focused on his mental condition as a newly discharged Vietnam War veteran with PTSD. He settles in Manhattan and starts driving cabs. The majority of the movie follows his transformation into a murderer and serial criminals while also highlighting his rescue of Jodie Foster’s Iris, a local child prostitute. While the conclusion suggests that Travis has become more psychologically stable, the director drops an artistic bomb in the final moments of the movie.

The unsettling, highly colored image of Travis staring back at himself with a wildness engulfing him forces us to reevaluate our ideas about how trauma heals. Travis is an intriguing antihero since, despite having the correct intentions to defend a victim of exploitation, he is appealed to violence as a way to address what he perceives as a structure of escalating social and economic issues. His lack of access to assistance or counseling worsens his mental instability. He makes plans to assassinate Leonard Harris’ Charles Palantine, a local political candidate. In a sense, Travis’ worldview is that of a man of anarchy, yet in reality, he’s having a hard time identifying who he is in a fresh city context, specifically 1980s NYC, on his own, after going through the war trauma, on the other side of the globe.

Iris is one of the 2 females Travis has meaningful ties with, throughout the movie, as the other is Cybill Shepherd’s Betsy, a volunteer for Palantine. Following a disastrous meeting with Betsy, he decides to assassinate Palantine and makes a scene in her volunteer office. His interpersonal fury begins to mix with his systemic one, causing him to engages Iris in prostitution and uses their time together to attempt to persuade her to stop. Travis’s violence rapidly ramps up in volume. He attends a protest in order to have Palantine shot, but Secret Service agents spot him carrying a weapon. Travis leaves and subsequently travels to look for Iris, murdering her customer, her pimp and the brothel bouncer, securing her.

At the conclusion of the sequence, Travis points his finger to his head, implying his suicide attempt. The inference is that Travis lacks a yardstick by which to assess if what he’s done that evening were right or wrong, or if he’s actively working to alter the urban for the better, or contributing to the corruption he deeply hates that surrounds him. He believes that his life may or ought to be finished.

The movie’s conclusion provides both of these partnerships with originally encouraging concluding remarks. Travis transforms into a local hero for liberating Iris and escapes prosecution for the killings. He also receives a message from Iris’ dad explaining gratitude for watching out for his daughter. Travis picks up Betsy and returns to his job as a cab driver after recovering from his wounds. He definitely has the emotional upper hand in this argument, it’s safe to say. Contextualizing that unrestrained moment of self-realization that occurs soon following their interaction stops requires a comprehension of his mental state.

It seems that Betsy still likes Travis, or at the very least, she regrets how terribly the relationship ended. She initially did like him. Betsy would have a sense of being closer to Travis once more after learning that he protected Iris; it’s as though they have similar ideals and stand on the same position. For his side, Travis maintains a polite distance from Betsy, refrains from trifling, and even expresses that he wants Palantine to triumph. Travis also has the final say, making a show of paying the meter for Betsy’s trip while she tries to talk about their memories and eventually questions the amount of money she’s indebted to him. Travis suggests with a smile that their interaction was sort of both something and nothing to him, but that he is now liberated—not just from her, but also from the emotional rollercoaster he went into with her.

Travis feels satisfied as he starts to back away. He is traveling by car in the city, which may no longer terrify him as much. He watches a part of himself as he looks in the rearview mirror while still driving. The moment his forehead, brows, and eyes are shown, the scoring changes to ominous. The camera moves quickly. Then, as Travis’ point of view returns, we can once again observe all the brightly lighted street signs, yet something has changed.

Travis recognized himself, but not the Travis he had anticipated. What lies beneath his composed demeanor with a quasi-ex? How at ease is he with reflecting about his near-assassination of her candidate in the past? It almost seems as though his pleasant demeanor with Betsy conceals the remnants of his fury and the fear of that rage. When Travis looks at himself, he still recognizes the person who is poised to attack with shocking brutality. It is obvious after watching this dissonant finale to know the reason Scorsese’s Taxi Driver keeps having an impact on modern directors.