A kid’s birthday invite turned into a full-on schoolyard mind game.

One mom thought she was dealing with a simple, painful classic: invitations handed out at school, the whole class included, and her 10-year-old daughter left as the lone exception. The catch, her daughter is autistic, struggles socially, and has a long history of clashing with classmates. So when the teacher offered to “mediate,” Mom didn’t jump at the chance to go full Mama Bear.

Instead, she hesitated, asked her daughter a question that hit like a brick, and decided she would not force a kid to invite someone he dislikes. That choice instantly earned her some heat at home, plus a few “Why aren’t you fighting for me?” tears from the child who felt singled out.

Then the update landed and it made the whole situation darker, messier, and way more personal than an invite list.

Now, read the full story:

This one hits in a very specific place, because it starts as “party invite drama,” and then it turns into “a kid deliberately twisting the knife because he feels nobody protects him.”

This one hits in a very specific place, because it starts as “party invite drama,” and then it turns into “a kid deliberately twisting the knife because he feels nobody protects him.”

I also get why the mom froze. She’s juggling two truths at once: her daughter feels genuine pain when she gets excluded, and her daughter also causes real pain when she lashes out. That combo can make a parent feel like every choice is wrong, because comfort can look like enabling, and consequences can look like cruelty.

Still, that last update line, “I want to let her feel bad,” gives me pause.

Natural consequences can teach. Revenge parenting tends to leave scars, especially for a kid who already struggles with social cues and empathy.

And that’s where this gets bigger than a birthday party.

School policies about invitations exist for a reason: kids experience exclusion as a social threat, not a mild inconvenience. Research on ostracism repeatedly finds that being left out can quickly damage a person’s sense of belonging and self-worth, even when the exclusion seems “small.” In one widely cited review, researchers note that ostracism reliably lowers feelings of belonging, self-esteem, control, and meaningful existence.

Now add the classroom context. Plenty of students get bullied. In the U.S., about 19% of students ages 12–18 reported being bullied during the 2021–22 school year. That matters here because both kids can carry real harm into this situation, and the adults have to deal with it without turning it into a moral scoreboard.

The mom’s initial instinct, “I’m not forcing an invite,” aligns with a basic principle: nobody should have to host someone they fear or resent at a private celebration. Even StopBullying.gov defines bullying as unwanted aggressive behavior that involves a power imbalance and repeats, or has the potential to repeat. If Bob experienced a serious bullying incident, pushing him to include the person who harmed him can feel like the school prioritizes rules over safety.

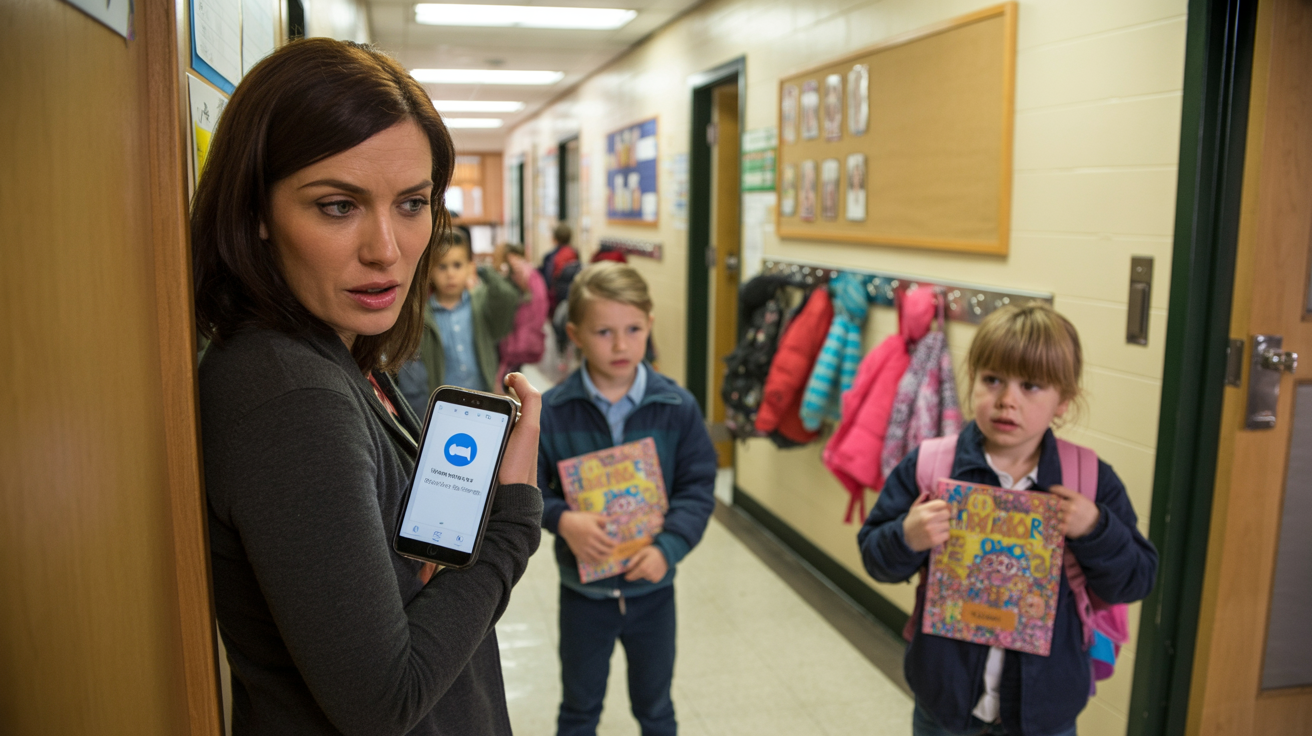

But here’s the twist that makes the update so important: Bob did not actually invite the whole class. He staged it, then lied to the autistic child specifically to hurt her. That crosses from “I set a boundary” into “I targeted you.” It also shows planning, social awareness, and intent. In other words, it is not just exclusion, it is a social retaliation.

So what does a fair, useful response look like?

First, separate the goals. The goal is not to get the autistic child into the party. The goal is to stop humiliation rituals at school, document bullying, and build safer peer dynamics. That means the adults should treat Bob’s behavior as a problem without dismissing his reason. Kids retaliate when they believe adults will not protect them. If his claim is true that “no one takes action,” the school needs a reset.

Second, the mom can teach empathy without running a “you deserve to suffer” campaign. Her daughter struggles with communication and says mean things. The mom already recognizes therapy and support. Great. Now she can tie the lesson to cause and effect in a way a 10-year-old can actually digest: “When you hurt people, they avoid you.” That teaches social reality. “You deserve to feel bad,” teaches shame, and shame tends to trigger defensiveness or spirals, especially for kids who already melt down under social stress.

Third, put structure around repair. If the daughter bullied Bob, she needs consequences at school, yes. She also needs a pathway back to belonging. That can include a supervised apology when appropriate, social skills coaching, and specific behavior goals, like practicing neutral language, taking breaks before escalation, and learning “exit scripts” for conflict. Autism can complicate social learning, but it does not erase responsibility. It changes how you teach.

Fourth, the school needs a practical plan for invitations. Many schools solve this by requiring invitations to go through folders, email lists, or parent-to-parent contact. That prevents public “show invites” in front of kids who are not invited. It also reduces the temptation for revenge performances.

The core message here feels brutally simple: exclusion hurts, bullying hurts, and retaliation hurts too. Adults can hold all three truths and still respond with fairness. That starts with accountability, plus a realistic bridge back to safer social behavior, not a punishment victory lap.

Check out how the community responded:

A big chunk of commenters basically said, “No one owes an invite,” and praised Mom for refusing to force a party guest list.

Others agreed with Mom’s boundary, but still wanted the school involved so this “invite exclusion” stunt stops happening in class.

A third group zoomed in on the bigger pattern and basically said, “This isn’t about autism, it’s about being mean and then being surprised people avoid you.”

This story has two kids trying to survive a messy social ecosystem, and a bunch of adults trying to decide what “fair” means when feelings and harm run in both directions.

The mom’s first instinct, refusing to force a party invitation, makes sense. A birthday party isn’t a public utility. If the relationship between the kids already feels hostile, shoving them together for “inclusion” can blow up in everyone’s face, including the other guests.

The update complicates it. Bob didn’t simply leave her out. He performed the exclusion, lied about it, and aimed for maximum embarrassment. That signals a deeper classroom problem, where retaliation starts to look smarter than reporting.

The best outcome probably lives in the middle: hold the autistic child accountable for harm, protect her from public humiliation tactics, and push the school to enforce rules consistently.

What do you think? Should schools ban in-class invitations altogether? And if a kid retaliates because adults ignored earlier bullying, how should the school respond without rewarding revenge?