Social gatherings are usually meant to be easygoing. For many young women, dressing up can be a simple way to enjoy the night without deeper intentions attached.

That sense of ease didn’t last for this 21-year-old after a casual house party took an unexpected turn. What began as a normal evening slowly shifted once someone else’s behavior became impossible to ignore.

Instead of focusing on that discomfort, blame landed somewhere else entirely.

This situation taps into a broader cultural conversation about clothing, confidence, and how society interprets women’s appearance, especially when someone other than the wearer projects meaning onto an outfit.

In this case, the OP chose a black dress that was tight and short because it made her feel confident and comfortable. She did not seek attention, flirt, or act provocatively toward anyone at the party.

Yet her friend’s boyfriend repeatedly stared and made sexualized comments, which made the OP uncomfortable. Instead of addressing her boyfriend’s behavior, the friend centered her own discomfort on the dress the OP wore, labeling it disrespectful.

This raises a key issue: does clothing inherently invite certain reactions, or do observers project meaning onto it based on their assumptions?

Research suggests that clothing does influence self-perception but does not automatically turn someone into a sexual object.

Studies in fashion psychology show that attire can significantly affect mood, confidence, and how the wearer feels about themselves, a concept referred to as “enclothed cognition.”

For example, research indicates that clothes symbolically shape identity and can deepen self-confidence or social presence.

At the same time, psychological research on sexual objectification makes an important distinction: revealing clothing does not inherently cause objectification; it is how others perceive and interpret it that drives objectifying responses.

In a study summarized in Psychology Today, researchers found that suggestive postures, not merely revealing clothes, contributed to objectifying perceptions, underscoring that attire alone does not dictate how someone should be viewed.

Another foundational idea in gender studies is the male gaze, a concept originally from film theory that describes how women are often viewed through a heterosexual male perspective that emphasizes appearance and sexualization rather than autonomy.

This gaze can have real emotional consequences, influencing how women feel about themselves and how others treat them in social spaces.

These perspectives collectively challenge the notion that a choice of clothing, even one that is form-fitting or styled to feel attractive, is a deliberate sexual invitation.

Clothing expresses identity and can influence confidence and mood, but it does not relinquish a person’s agency over how they ought to be treated.

The reaction of the friend’s boyfriend illustrates this very point. His stare and comment were his behavior, not the OP’s action.

The discomfort he felt, and that was projected onto the OP’s dress, stemmed from his perception, not the objective nature of the outfit itself.

Blaming the OP for her clothing choice shifts responsibility away from the person whose gaze was inappropriate, and onto the person who was merely wearing something that made her feel good.

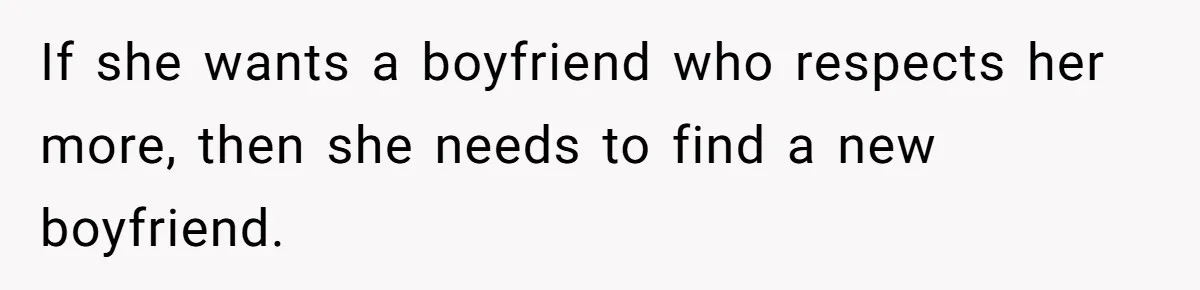

Advice in situations like this is to help recenter the conversation on behavior and respect, rather than on attire alone.

The OP might explain that her dress was a matter of personal expression and confidence, not an invitation for attention.

She could gently point out that unwanted staring or commentary made her uncomfortable, and that the friend’s focus on her clothing sidesteps the real issue: inappropriate attention from a third party.

This story ultimately reflects a deeper cultural pattern: women are often held responsible for managers’ reactions to their appearance, rather than holding observers accountable for how they choose to look at and treat someone.

Clothing does influence how a person is perceived, but perception is shaped just as much, if not more, by cultural norms and ingrained biases about gender and sexuality.

The OP’s experience highlights how quickly external interpretations can overshadow personal intent, and why respectful communication and mutual understanding often matter more than what someone is wearing.

Take a look at the comments from fellow users:

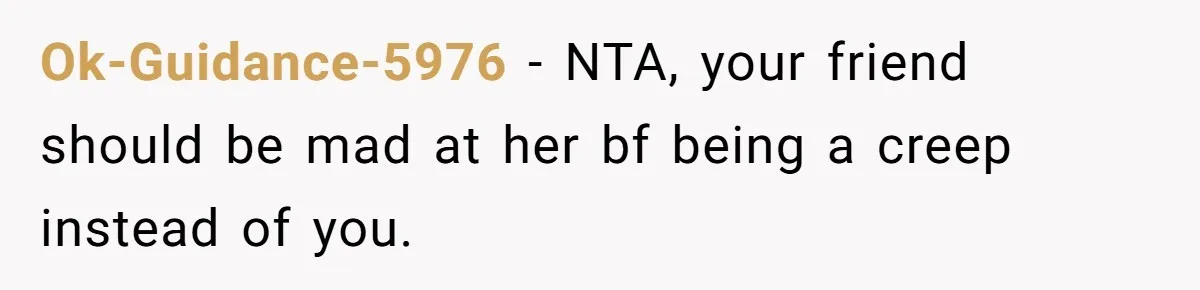

This group firmly backed OP and called out the misplaced blame.

These commenters leaned into the “friend problem” angle.

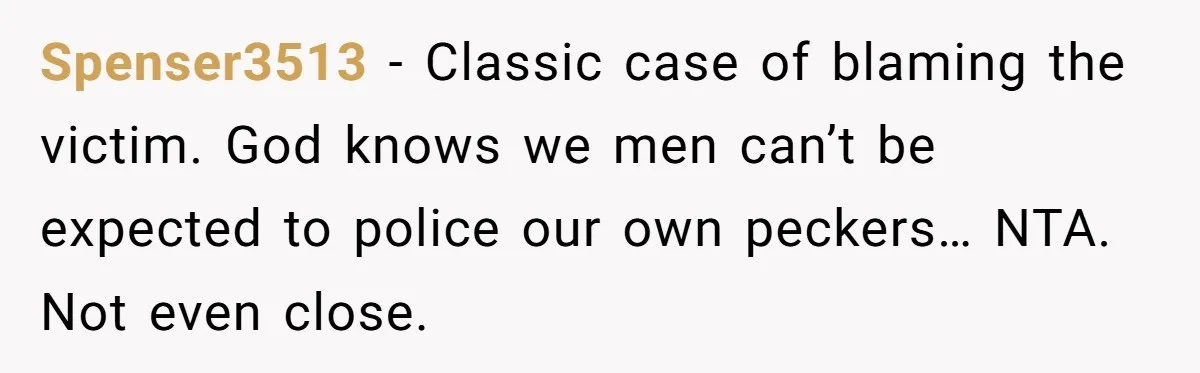

This group didn’t engage with the moral debate at all. Instead, they accused the post of being a repost, karma farming, or low-effort bait.

Taking a more critical stance, this commenter argued that context matters.

This story hits a nerve because it’s painfully familiar. Do you think outfit choices ever make someone responsible for another person’s behavior, or was this misplaced blame all the way?

How would you handle it if a friend asked you to apologize for someone else’s wandering eyes? Share your take.