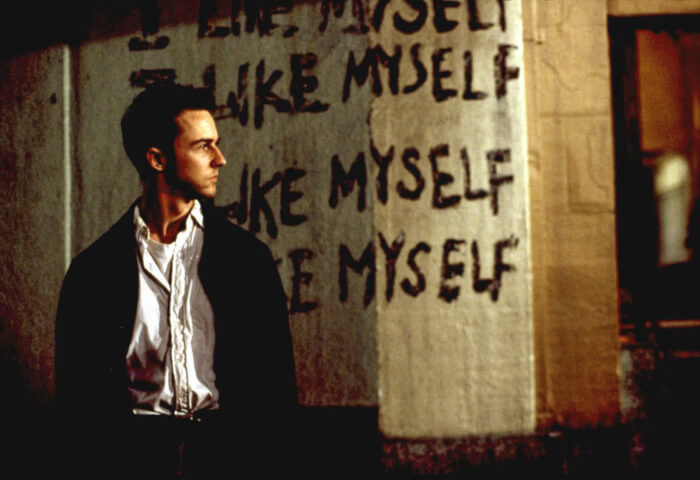

Reflecting on David Fincher’s most misinterpreted movie is the next step in our Fincher retrospective.

The first rule of Fight Club is: you do not talk about Fight Club. The film, which did poorly at the box office, gained new life on DVD, where it rose to fame. Within the movie’s settings, Tyler Durden‘s well-known rule is a clever and humorous marketing ploy for a group of guys looking to avoid advertising and link with others. The tale of Fight Club has been severely misunderstood by every viewer who watched the film and had this thing come to my mind, “I should establish a fight club!”, through the lens of Tyler, though the Narrator was the de facto storyteller. The film doesn’t admonish. It’s not a David Fincher rant full of rage or Tyler Durden Church worship. Even the idea of male bonding isn’t the only one. Only David Fincher could turn Fight Club into some sort of romantic comedy.

Fight Club, much better than any of Fincher’s rest films, lends itself to the broadest range of interpretations due to its extensive subject matter. It seems paradoxical that a director with a reputation for accuracy would cast such a wide thematic net, but screenwriter Jim Uhls (with an uncredited help from Se7en screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker) made an excellent job of turning the scope of Chuck Palahunik’s complex novel into a practical script.

One could interpret Fight Club as a protest against consumer culture.It may be a critique of a generation that has been lost. It may be about reducing ourselves to our most fundamental instincts. It may even be an anarchist celebration. The movie is clear enough to give this information but not so vague in order to leave room for analysis, so it might be one of these things and more. But after my latest watch, I’m now certain that Fight Club is among the most bizarre, humorous, deceiving, and wicked love tales ever depicted on television.

Brad Pitt’s Tyler Durrden may be our seducer and Edward Norton’s The Narrator may be our main character, but Helena Bonham Carter’s Marla is the essence of the whole film. Tyler is shortly sliced into every film frame prior to the moment Marla is introduced to us. Tyler’s already presented in The Narrator’s mind, but just in a split second. Before they actually meet, The Narrator believes the fabricated community of support groups has brought him serenity. For him, the organizations don’t represent true relationships; instead, they fill the void that keeps him up at night. His remarks about Chloe, who had end-stage cancer: “Chloe looked the way Meryl Streep‘s skeleton would look if you made it smile and walk around the party being extra nice to everybody,” make it certain that he has zero sympathy for everybody else, if the fact that he crashes support groups isn’t enough. After that, Marla is introduced to the movie and, “She. Ruined. Everything.”

She wrecks everything because The Narrator has a crush on her. He claims, “Her lie reflected my lie.” She is a kindred spirit for anybody who is still too absorbed in themselves to truly link with anyone. His flat is full of stuff, yet all that’s in his fridge are only condiments. He’s unable to prepare food, and lacks somebody with whom to share it. Similar to any grade-school guy who wants a girl, he kicks Marla in the shins and pushes her away when she reflects his emptiness back at him. He is unable to feel close to a real person.

Here comes Tyler Durden. The Narrator is being guided by Marla toward the realization that he needs a true relationship, but as his phony relationships at support groups start to fall apart, a completely false connection is even more beneficial. The Narrator has “woken up as a different person” when he and Tyler first meet, and that person immediately calls him up on his bullshit. Tyler is attractive right away since he is aware of The Narrator’s thinking. The Narrator may not be able to explain to us why he called Tyler, but it is obvious that he did it on purpose to make a subconscious friend—someone who would force him to take stock of his life rather than offer him a yin-yang table or some sort of soft support and backup.

Their very first altercation is the culmination of their union. The Narrator feels a mixture of self-love and self-hatred trapped within himself. Prior to the beginning of the film, however, he gives away some crucial plot points and allows Fincher to shortly enter the frame to warn us about the anarchic soul that is bound to erupt (not that it wasn’t already intimidating to deluge thanks to the remarkable VFX work, dark humor, and sliding penguins). According to what is said, Tyler is a projectionist who enjoys sneaking pornographic scenes into films. In addition to mentioning Tyler’s prior appearances, the phrase “No one knows they saw it, but they did” also serves as a warning about the way Fincher will continue to leave hints that The Narrator and Tyler are in fact the same person.

Of course, there are undisguised instances in which The Narrator speaks to the detective using a phone, and Tyler says inaudibly “Tell him the liberator who destroyed my property has realigned my perceptions,” when he’s inquired about a potential suspect. And Tyler also says, “who reject the basic assumption of civilization, especially the importance of material possessions,” when asked about foes and The Narrator replies, “Enemies?”. We are, repeatedly, provided with these hints. The Narrator informs viewers that he is reminded of his initial confrontation with Tyler when he self-humiliates in front of his employer. These brief exchanges add up, particularly as Tyler and The Narrator discuss their respective lifestyles.

They discuss an absentee dad giving advice as Tyler’s bathing and The Narrator is trimming his fingernails. They heed the first piece of guidance: enroll in college. They heed the second piece of advice: find employment. However, with regard to the third piece of guidance: get married, The Narrator responds. “I can’t get married. I’m a 30-year-old boy.” As a result, The Narrator falls into teenage illusions rather than chasing after Marla in the right way.

He decides to beat up other males and delegate the sex to his fictitious pal. Despite the fact that Marla and the Narrator are a wonderful match, the Narrator finds it difficult to accept the idea of an emotional bond. Keep in mind that Tyler and Marla never share a place with The Narrator. Never are the 3of them in the same space. Again, the twist plays a role in this, but other factors include the warring parts of the dark, twisted Peter Pan that tempt him to hang around with lost boys and a woman who may be seriously messed up yet is attracted to The Narrator despite his inability to see it. He only notices a memory of his parents and a feeling “like a six-year-old again.” It’s unnecessary for us to have a flashback to The Narrator’s early years since he has already revealed everything that is essential for us to know, including the fact that he has no concept of what a love relationship entails in terms of maturity. It is far preferable to simplify life by attacking other damaged individuals and taking advantage of their anxieties and self-doubts.

Fight Club is the ideal seduction because of Fincher’s artistic talent. We witness the filmmaker’s extraordinary talent for transforming the ugly into something weirdly beautiful, in addition to the skillful casting of Brad Pitt, a handsome actor adored globally. It is distinguished by frequent comedy as well as by the dark violence. Tyler Durden is obviously attempting to charm us because Fight Club is so darn entertaining.

Tyler Durden is trying to win us over to his cause. Fincher expresses sympathy for the creative master planner once more. This is the reason a number of audiences interpret the film incorrectly. The movie is not a quest announcement, not a manifesto, not a treatise, and not an appeal for violence. One may argue that Pitt and Fincher are being hypocritical by doing advertisements while the movie despises capitalism. First, Fincher says in the commentary track: “This film probably more accurately depicts my take on advertising and what it provides for society [laughs] than any—you work where you can. I’d much rather start off making movies, but no one was much interested in hiring me to make movies early on, so I did music videos and commercials as a way to just play with the tools.”

Tyler makes a subtle personal innuendo by saying, “The things you own end up owning you.” It appeals to our awareness that maybe we rely too much on materialism. We ought to yearn for freedom in some way. But to dismantle everything as if consumerism were the cause of all of The Narrator’s or our troubles is an infantile tendency. This cliché serves as a way to prop open the door a little bit further so that, like any good cult, the leader can continue to radicalize things.

The moment Fight Club transforms to Project Mayhem, The Narrator is no longer concerned with escaping. It’s becoming worse, and his naive wishes have spread. Tyler is now The Narrator’s enemy after his buddy turned into a father figure for him. The Narrator breaks his pledge to Tyler and refers him to Marla when she arrives. Marla is naturally perplexed by the revelation that “Tyler’s not here. Tyler went away. Tyler’s gone.” For the first time in the film, The Narrator shows vulnerability around her as opposed to obnoxiously shoving her away. Ironically, The Narrator only recognizes all of the “You are not a beautiful and unique snowflake” or chemical burns have anything to do with his genuine difficulties after adhering to his own maxim, “It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything.” It has come to the moment for The Narrator to leave once Bob passes away and it appears obvious that the cult is now maintaining itself, and that’s when he introduces the twist.

According to Marla, Tyler Durden is The Narrator himself. Even while the bartender might have mentioned this before, only Marla could truly understand and link up what was being stated. And The Narrator responds, “So we did make love,” when Marla questions whether they only had sex or made love. This is the same man who, in the past, delighted in the concept that Marla would gradually kill herself and who, at the mere prospect of being in her company, wanted to decorate the walls with his brains. David Fincher is the only filmmaker able to create a movie as joyous, anarchic, sardonic, wry, winking, and twisting as this one. It contains all the components we anticipate from Fincher, but The Curious Case of Benjamin Button serves as an unexpected case study that demonstrates how underappreciated his heart is, and we will come to that movie discussion later. Underneath all the bravado, chest-beating, caustic criticism, and statements in the stinging, highly quotable, acerbic, meaty movie Fight Club is a narrative about putting all that nonsense aside for something real.

Tyler Durden is just a myth. He is not real. He is a boisterous spirit who finally feeds our baser inclinations, forcing us to either be at his mercy or by his side. The Narrator isn’t able to embrace Marla until he makes the decision to kill his invented buddy —his embodiment of irresponsible youth—in the head. The Narrator informs her, “You met me at a very strange time in my life.”

When buildings start to blow up, they hold hands because even though love can’t stop the world from ending, it’s still good to have someone by your side as it does. Tyler, however, remains very much a part of this world. Tyler Durden may have been set free by The Narrator, but he is still a concept, a concept that has endured well beyond the confines of the film, influencing everyone who regards them as gospel, instead of mere populism. Since Tyler’s universe is where we are now and will always be, Fight Club still appears to be the same at the conclusion.

The charm of rejecting every present-day idea, reverting to our primal impulses, and choosing to be let loose of the lifeless office job and the inexpensive furniture will always remain. Tyler continues to present the film to the audience. The man stays inside the projection booth, and what do we hear before the credits appear? “Nice big cock.”

Themes-wise, Fincher’s next film would be a little easier to understand, but it would be much harder to make.