“I have to believe my actions still have meaning even if I don’t remember them.”

One of my pet peeves in the movie industry is the moment everyone dubs the plot of Christopher Nolan’s Memento “a gimmick.” Gimmicks are hooks that have no purpose. It grabs your notice yet, by definition, offers no reward. It might have been a gimmick if Nolan had Guy Pearce wear a chicken outfit the whole time and never clarified why. Memento‘s effectiveness comes from its reverse chronology since it is the only method to bring the audience in the thoughts of its brain-damaged main character Leonard Shelby. The reverse chronology does draw you into Leonard’s realm, where we witness consequence without root and can only see the strength of causality as we travel farther back in time, just like how Burt (Mark Boone Junior) remarks in one of the movie’s more meta moments. Due to Nolan’s masterful ability to beautifully intersect time, identity, and memory into his best work, Memento‘s distinctive structure gives the film a hook and its strength.

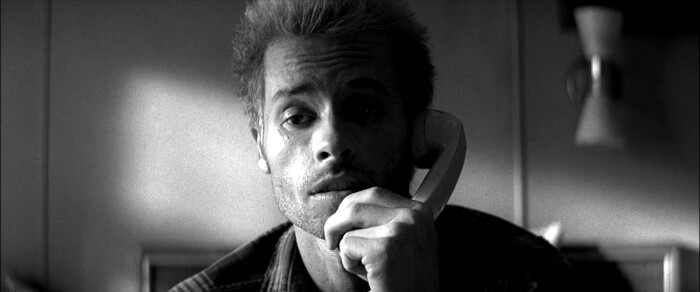

The narrative centers on Shelby, whose amnestic syndrom results from a break-in at his home, which also led to the sexual assault and killing of his spouse. From the time of the incident, Leonard has been pursuing the perpetrator, but his pursuit is hampered by the inability to form new remembrance. Leonard then persuades himself that he can be properly disciplined to exact revenge through conditioning. However, as the plot develops, it becomes clear that Leonard is actually running after his own ghost rather than the real criminal. He has been deliberately constructing a puzzle that he might not ever unravel since he has already done it, but he let it slip that he has already avenged himself. What’s worse is that everyone he comes in contact with uses him, from Mark Boone Junior’s Burt – the clerk at the inn’s front desk, to Carrie-Anne Moss’s Natalie, the vengeful bar waitress, as well as Joe Pantoliano’s Teddy, the crooked police officer. Leonard holds onto the illusion of control he thinks he has, but it’s only a delusion. He views his tattoos and Polaroids as irrefutable proof, although they are just as subject to error as his recollection. In the final moments of the movie, before forgetting everything one more time, Leonard finds out that his spouse didn’t die after the attack, but killed herself by allowing him to overdose her with insulin injection.

The character of Leonard Shelby, a guy assuming he’s able to control only to discover that his authority was delusive, recurs in Nolan’s filmography, but it works especially effectively in Memento due to the way Nolan is able to subvert noir genre preconceptions. Leonard is our investigator, and even though he has a disabling condition, he should still be capable of resolving the case. However, as the movie progresses, it becomes clear that Leonard isn’t seeking justice or even retribution; rather, he is holding onto the remnants of an identity. He has trained himself to avoid cracking the case and instead to recreate a replica of his previous existence as an insurance investigator (yet another reason he can’t restrain himself from mentioning Stephen Tobolowsky’s Sammy Jankis). Leonard has created a complex hoax that enables him to maintain his identity and live out the same illusion of being able to solve a mystery. Leonard is the one who is lied to by everyone.

The fact that Memento understands we all deceive ourselves lends the tale its power. Simply said, Nolan found a way to make the act of lying one of the movie’s main factors. Leonard isn’t inflating his ego or his accomplishment in his own eyes. His brain impairment permits him to continue perpetuating this mythology despite the fact that he is deluding himself on his own identity. Only when we think back to the opening scene do we realize Leonard has a fresh chance to end the cycle. Perhaps Leonard will whisper to himself the truth if Teddy is no longer there to use Leonard as a tool and there is a fresh photograph documenting Teddy’s death. Maybe it will stop the cycle, but before we arrive at that conclusion (which occurs right away), we need to realize the movie’s central theme, which we may only do once we know the reason Leonard murdered Teddy from the beginning.

Leonard aspires to believe that his acts have purpose, just like everyone else. Although he asserts that “The world doesn’t just disappear when you close your eyes,” he has really grown somewhat detached from it since causation has been disrupted in his thinking. The film Memento is a potent tale about the force of identity and the way it is capable of surviving amnesia. Even though Leonard is certain about his identity, it’s not until the conclusion that Teddy informs him, “That’s who you were.” Leonard is unable to acknowledge that, in the absence of his revenge and the need to resolve a puzzle, he is merely a man with brain injury who likely has no position in society. Instead of remembering the events that occurred to his own wife who committed suicide, he fabricated a consoling story about Sammy Jankis.

It’s great how all of this is assembled within a neo-noir framework, and viewing Memento is like witnessing a house of cards that, you know, may fall at any second. However, Nolan and editor Dody Dorn are experts at knowing precisely where to cut the action and how to flawlessly assemble the story so that the viewer is never disoriented. Nolan isn’t aiming to alienate his viewers with Dunkirk, Inception, or any other of his films that manipulate time, including Following. This is not Primer, in which you can just surrender yourself and go along for the ride. In order to make sure that you understand that you are seeing Leonard in a narrative that is distinct from the reverse-narrative, which goes on till both storylines converge at the movie’s finale, Nolan comes to the point of having his prologue be in black and white.

The control over time contrasts neatly with Leonard’s delusion of control over his own story. Nolan movies are preoccupied with the idea of control. The degree to which Nolan and his main character exercise control over the force of narrative is where they mesh. The idea of storytelling and how the ability to create is intrinsically related to destruction intrigue Nolan. Since his creation depends on a lie, Leonard has developed a totally new self that is predicated on destruction, leading him to become nothing better than Teddy’s assassin. Leonard has given his own identity a cozy deception, and like The Young Man from Following, Robert Angier from The Prestige, or Mal from Inception, that deception has demonstrated to be his demise until he eventually resolves to seek something that is right all along, he’s been manipulated by Teddy, and so his manipulators must be thwarted.

Leonard Shelby’s self-deception, regardless of his particular situation, is universal, as shown in the cautionary story of Memento. Nolan isn’t against the idea of a deception; after all, he tells stories. But he finds the execution of lying to be fascinating. To the director, lies are just tools, and they can occasionally be employed for good, as the magic tricks in The Prestige, or the mind heist in Inception.

The claim that Teddy was accountable for the assault and death of Leonard’s spouse is shown to be a new deception in Memento, but like all great art, it is a deception that speaks the truth. Teddy might not have caused Leonard’s illness, but he is, to some extent, to blame for Leonard’s plight because of his manipulation of Leonard as a tool. Teddy informs Leonard, “You don’t want the truth. You make up your own truth.” The truth Leonard ultimately chooses to believe in is that Teddy has to be stopped, and the reason for this is irrelevant since Leonard won’t ever recall the causes. Leonard assures himself he’s not a murderer, weaving a web of good motivations around his lies. But even if he cannot recall his deeds, they nevertheless have significance.

Christopher Nolan created a film where the lie itself served as the lead through clever character development and planning. The main paradox of Leonard Shelby is that, while having truth-seeking intentions, he only ever consumes lies rather than everything else. The reality can be so painful that he even trains himself to succumb to more lies. “You lie to yourself to be happy… We all do it!” Teddy shouts to him. But to paraphrase a later Nolan movie, “Sometimes the truth isn’t good enough. Sometimes people need something more. Sometimes they need their faith rewarded.” Leonard Shelby finally discovers that he must continue to think that his activities still have purpose. The reality he needs isn’t that he’s turning himself into a vindictive being. Before the opening credits roll, we’ll find out if his falsehood causes him to discover a more beneficial truth.