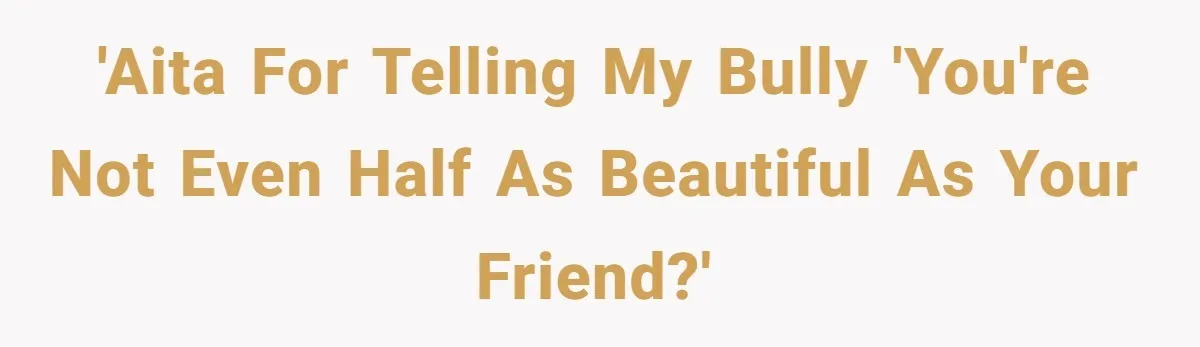

Bullying can hurt, but sometimes, retaliation feels like the only way to fight back. This is exactly what happened when a young man, tired of being called ugly by his classmate Clara, finally snapped.

Clara had been taunting him for a while, first calling him poor and then progressing to calling him ugly.

One day, enough was enough. He snapped back with a harsh comment, telling Clara that she wasn’t nearly as beautiful as her friend, Kate.

While his friend laughed off the situation, Clara wasn’t amused and quickly became furious.

What the OP did in that moment, firing back at Clara with the comparison to her friend, didn’t happen in a vacuum.

The situation illustrates a broader behavioral pattern seen in peer interactions where repeated verbal teasing or belittling can escalate into conflict rather than resolution.

Children and teens who experience ongoing name‑calling or ridicule are often driven to respond emotionally, which can inadvertently reinforce the dynamic rather than de‑escalate it.

Studies of bullying behavior show that when a target responds with aggression or emotional retaliation, it can actually prolong or intensify the cycle of victimization rather than stop it.

This is because bullying, by definition, involves an imbalance of power and repeated harm, and reactions that mirror aggression may subtly reinforce that dynamic rather than undermine it.

Bullying researchers like Dan Olweus, often considered a foundational figure in bullying research, define bullying as unwanted aggressive behavior that involves a power imbalance and repeated harm.

Responses that involve aggression or retaliation can provide temporary emotional relief but seldom change the underlying social dynamic or power structure.

From a psychological standpoint, the effectiveness of any response to repeated insults or teasing should consider intent, power dynamics, and communication goals.

The existing evidence on bullying responses highlights several important patterns.

For example, research has found that victims who rely on assertiveness, avoidance, or seeking help from a third party are more likely to interrupt bullying behavior than those who respond with anger or revenge‑seeking.

Angry responses often correlate with a cycle where both parties continue to escalate.

Social psychologists also note that teasing, insults, and put‑downs can be a form of verbal aggression that is harmful to one’s self‑concept.

When bullying takes the form of repeated verbal attacks, it can erode confidence and increase social stress, particularly if the target becomes socially isolated or cannot easily escape the environment.

In such situations, retaliation that highlights appearance or social comparisons may temporarily flip the power dynamic but rarely fosters long‑term resolution or mutual respect.

Another expert perspective comes from Finnish psychologist Christina Salmivalli, who studies peer dynamics and bullying.

Her work shows that bullying often isn’t just a single act, but a group process, where bystanders, peer status, and social norms all contribute to whether aggressive behavior continues.

Responses that escalate conflict, even when understandable, often fail to shift the underlying group perception or power structure that enables the bullying to happen in the first place.

That’s not to say the OP’s feelings aren’t valid. Being repeatedly teased because of something like a phone model, a vulnerability used as leverage, can be deeply frustrating.

Many people instinctively lash out when they feel demeaned or dismissed. But research suggests that retaliatory verbal aggression is usually ineffective at producing social change in a bullying dynamic.

It can sometimes momentarily silence the bully, but it often shifts the interaction into a cycle of mutual conflict rather than addressing the root cause.

The OP’s tactic was clever in its immediate impact, Clara did stop in that moment, but tactics like this rarely address chronic bullying effectively.

Instead, they sometimes inadvertently reinforce the very cycle they aim to disrupt.

At its core, this situation highlights a universal social lesson, reacting to repeated hostility with another form of hostility usually extends conflict, whereas strategies centered on assertive boundaries, support networks, and de‑escalation are more likely to change the pattern of interaction over time.

That doesn’t make the OP weak; it makes his response more strategic and sustainable.

Here’s the feedback from the Reddit community:

These commenters were fully behind the OP, applauding the witty and well-timed response to the bully.

This group took a more reflective stance, pointing out that the OP’s friend, who didn’t stand up against the bullying, might not be a good friend at all.

These users viewed the comeback as fair game, emphasizing that “turnabout is fair play” and that the bully had it coming.

![Guy Responds To Years Of Bullying By Telling His Bully She's Not As Pretty As Her Friend [Reddit User] − NTA. I don't condone bullying, but you served her a heaping slice of humble pie.](https://dailyhighlight.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/wp-editor-1766558062654-26.webp)

This group had a more sympathetic view of the OP’s position, acknowledging that the bully deserved some kind of response but also suggesting the possibility of moving on from this toxic friendship.

This situation is a reminder of how words can be weapons, even when you’re defending yourself. The OP clearly felt pushed to a breaking point after constant bullying and used a sharp retort to try and regain some control.

However, the line between standing up for yourself and sinking to the same level of cruelty is thin.

Was the OP justified in responding this way, or did they escalate things unnecessarily? How would you have handled the situation? Share your thoughts and opinions below!