Grief does not follow a neat timeline. Some days feel manageable, while others reopen wounds that never fully healed. For people navigating loss at a young age, milestones like birthdays can bring a complicated mix of love, sadness, and vulnerability.

In this case, a supportive group of friends tried to lift someone’s spirits during an emotionally heavy moment. What they didn’t expect was that one gift would completely change the tone of the night.

As messages began rolling in, the focus shifted from the gift to something deeper.

Grief is a deeply personal and highly variable experience that doesn’t adhere to a predictable or socially convenient timeline.

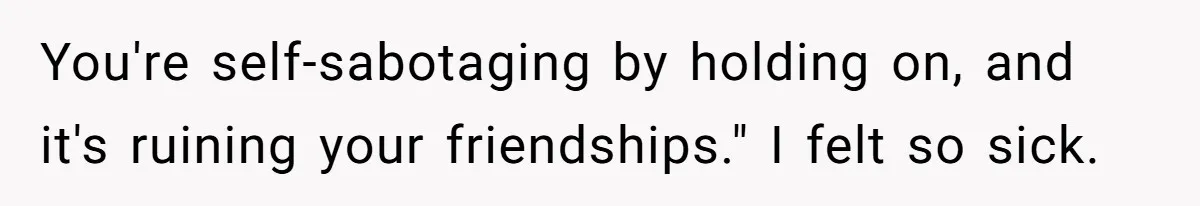

In this situation, the OP lost her mother suddenly eight months prior, a profound emotional rupture marked by unresolved feelings and continuing pain.

When her friend presented birthday gifts that turned her grief into a punchline, the reaction wasn’t simply emotional sensitivity; it touched the ongoing psychological reality of loss that research shows persists long after the initial shock fades.

Studies indicate that grief’s effects can endure for months or years, influencing emotional, cognitive, and behavioral responses long past the date of loss. Grief is not linear, and there is no universal endpoint at which someone “should be over it.”

This complexity is well documented in grief research, which notes that psychological distress can persist and even interfere with daily functioning long after a loved one’s death.

What many people misunderstand is that grief doesn’t simply fade with time.

Qualitative grief research highlights that individuals commonly experience intense emotional triggers, moments that suddenly resurface sorrow and raw feelings, often years after the loss occurred.

These triggers can be anything that has emotional resonance, including birthdays, reminders of shared experiences, or references to the deceased.

These reactions are not abnormal regressions; they are part of the unpredictable and individualized nature of bereavement.

Psychological frameworks also emphasize that there is no prescribed “normal” grief timeline. Reputable mental health sources explicitly state that the notion of a fixed period after which someone ought to “move on” is a misconception.

Each person grieves at their own pace and in their own way, and grief may ebb and flow unpredictably over time.

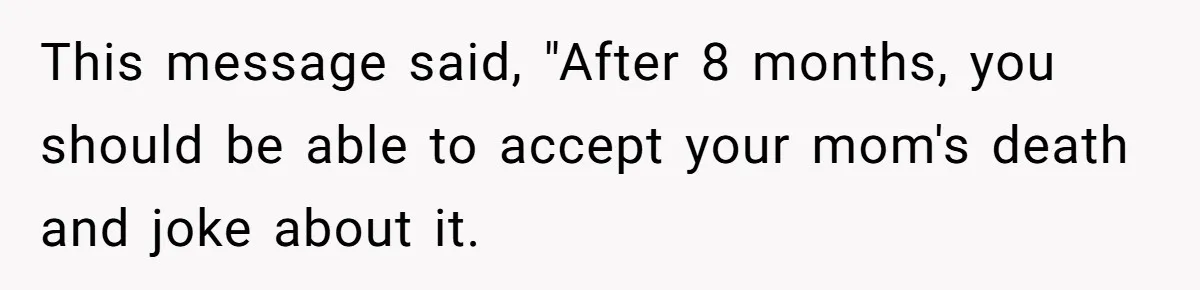

Attempts to impose a timeline often lead to grief invalidation, dismissing or minimizing the bereaved person’s feelings because they don’t align with others’ expectations.

One particularly relevant concept here is disenfranchised grief, a form of grief that is not socially acknowledged or validated. This can occur when friends or family attempt to regulate someone’s mourning by telling them they should be “over it” or find humor in the loss.

When social circles respond with pressure to conform to a certain way of grieving, the bereaved person can feel isolated, misunderstood, or ashamed of their natural emotional responses.

Validating a person’s grief, rather than dismissing it, is crucial for emotional recovery and maintaining trust in relationships.

Humor in grief is context-dependent. While in some settings people may eventually use humor as a personal coping mechanism, research shows that the use of humor to address death and loss carries significant risks when it’s not chosen by the person grieving.

Some studies note that gallows humor or humor related to death can be helpful in certain professional contexts (such as caregiving professions), where individuals use humor to cope with repeated exposure to loss.

But this doesn’t necessarily translate to personal grief experiences, especially when the humor is introduced by others without consent and directed at the source of someone’s pain.

Neutral advice in situations like this emphasizes empathy, listening, and validation over assumptions about how someone “should” feel.

Being present, acknowledging the depth of someone’s loss, and avoiding minimizing language helps sustain emotional well-being.

It’s also important to recognize that grief has continuing bonds, enduring emotional ties with the deceased that evolve over time but do not disappear entirely.

These bonds can influence thoughts, memories, and emotional responses long after the death, and forcing humor onto that experience can feel dismissive rather than supportive.

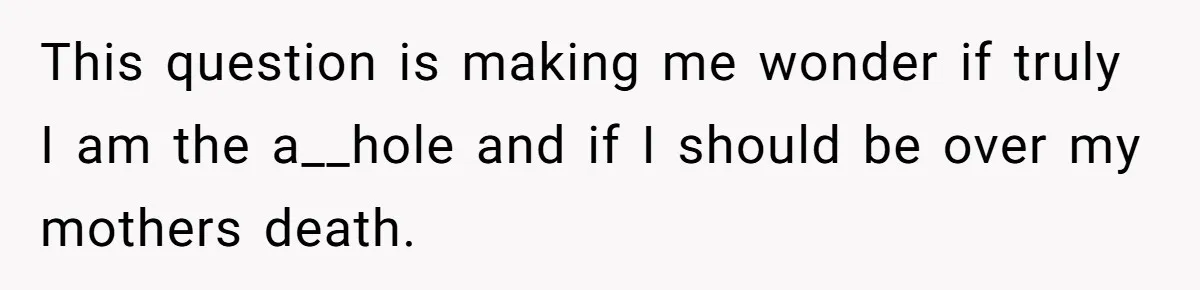

At its core, this situation highlights a widely misunderstood aspect of grief: time itself does not dictate readiness to joke, heal, or emotionally “move on.”

Healing is nonlinear, deeply personal, and shaped by individual psychological processes and support systems.

The OP’s reaction, pain, shock, and withdrawal, reflects this ongoing internal journey of loss, not a failure to “get over” her mother’s death.

Responding with empathy rather than pressure or humor aligns with what grief research identifies as supportive and respectful of the bereaved person’s lived experience.

Here are the comments of Reddit users:

These commenters spoke from lived experience with loss.

This group focused on consent and boundaries around grief.

These users zeroed in on Kayla’s reaction after the gift failed.

This group labeled the gift outright vile and rejected the idea that intent matters more than impact.

Sharing personal stories, these commenters illustrated how grief lingers in unexpected ways.

This wasn’t a joke that missed the mark. It was grief being turned into a punchline before the wound had even closed.

The Redditor didn’t lash out or make a scene; she simply shut down, which says more about the shock than any anger could.

Is eight months ever enough time to laugh about losing a parent? How would you have reacted in that moment? Share your thoughts below.