In many immigrant families, children often grow up taking on adult responsibilities far earlier than expected.

Language barriers can quietly turn a child into a bridge between worlds, carrying paperwork, phone calls, and decisions they were never meant to manage alone. Over time, that role can become so normal that no one questions the cost.

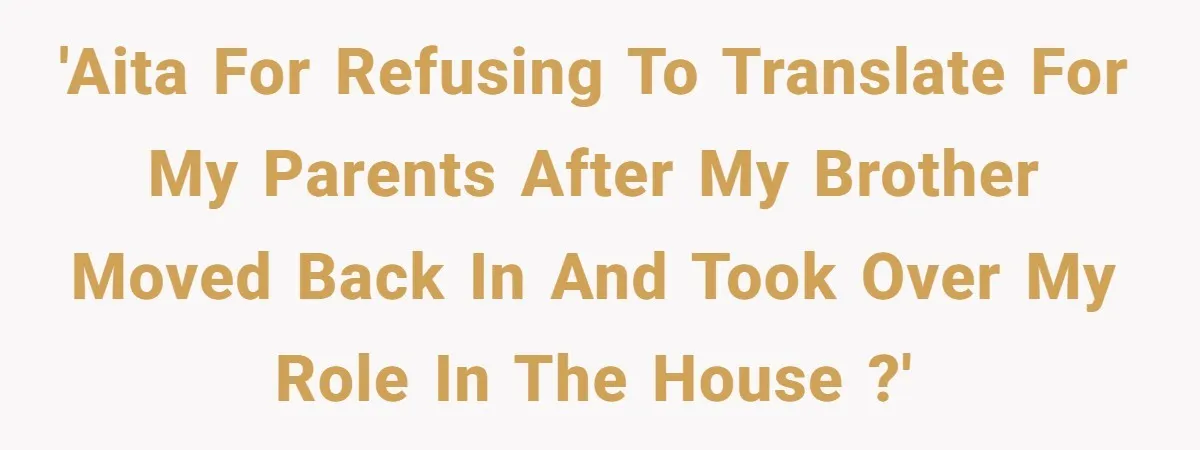

That is where this story begins. A young woman who has spent years translating and advocating for her parents suddenly finds herself pushed back into that role, even after her older brother returns home.

Despite another capable adult in the house, expectations remain unchanged.

The situation the OP describes, being the family’s de facto translator for most of her life and now refusing to continue in that role, fits into a well-studied phenomenon in immigration research known as child language brokering.

Language brokering refers to when children or young adult children of immigrants translate and interpret for their parents or family members in daily life, from school forms to legal appointments.

Researchers describe this as a common experience among immigrant families, especially when parents have limited proficiency in the dominant language of their new country.

It is not just occasional help; it can extend into long-term responsibility for navigating complex social systems on behalf of the family.

Academic work shows that language brokering places children in roles that are developmentally adult, requiring them to interpret not just words but cultural nuances, legal meanings, and bureaucratic expectations.

In many cases, young language brokers negotiate documents with schools, doctors, banks, or government offices, responsibilities that go far beyond casual translation.

This deep involvement can accelerate some aspects of maturity but also create stress, role confusion, and emotional burden, particularly when children feel ongoing pressure to carry these tasks without support.

Scholars have also noted that the effects of language brokering are complex and variable. For some young people, translating for family members can strengthen bonds, support cultural identity, and enhance bicultural competence.

For others, it can be a source of sustained emotional strain, especially when the child feels obligated rather than willing to take on the tasks.

This dual nature of language brokering suggests that experiences can be supportive in some contexts and burdensome in others, particularly when the responsibility is continuous and interferes with school, work, or personal life.

Language brokering also intersects with family dynamics in predictable patterns.

Research shows that older children and girls are more likely to assume language brokering roles, partly due to cultural expectations and parental reliance on them as the most linguistically capable family member.

This can create a generational and relational imbalance where the brokering child takes on tasks that parents could reasonably share or assign to others as siblings gain proficiency.

Another important piece of the research is the concept of the acculturation gap, the difference in language use, cultural adaptation, and day-to-day social expectations between immigrant parents and their children who grow up immersed in the host culture.

The acculturation gap can contribute to intergenerational conflict when children adopt the dominant language and cultural norms more rapidly than their parents, leading families to become reliant on the child for communication and navigation of mainstream institutions.

This dynamic can unintentionally shift expectations onto the child to shoulder responsibilities beyond their years.

In light of these findings, the OP’s decision to set boundaries around translating is not only understandable but also consistent with research highlighting the potential emotional costs of perpetual language brokering.

Her exhaustion, missed personal time, and sense of being “used” reflect what many language brokers report when the role becomes a taken-for-granted expectation rather than a reciprocal exchange within the family.

Neutral advice based on this body of work would emphasize that helping family members is valuable, but ongoing obligation without shared responsibility can lead to stress and relational strain.

Discussing boundaries with parents in a calm but assertive way, such as explaining that she will help when available but cannot rearrange her life around translation alone, can foster a healthier family balance.

Encouraging her brother to take on appropriate translating tasks when he is capable would reduce the disproportionate burden on her, and seeking professional interpreters for high-stakes appointments (e.g., legal or immigration meetings) would also relieve pressure and uphold accuracy.

Research suggests that redistributing these tasks can improve family cohesion and reduce the emotional load on the child language broker.

At its core, this is not about refusing to help family out of malice, it’s about acknowledging that lifelong responsibility for adult tasks is neither developmentally fair nor sustainable, especially when other capable adults are present.

Setting boundaries can preserve her well-being and still leave room for meaningful contributions within a balanced family dynamic.

Here’s what people had to say to OP:

These commenters immediately challenged the parents’ favorite line: “family helps without complaining.”

This group focused on systemic favoritism. They framed the brother as the golden child and the OP as the default fixer because she’s female.

Offering a more layered perspective, this commenter acknowledged fear, shame, and immigration-related anxiety on the parents’ side.

These users addressed the language barrier directly. They pointed out that interpreters are legally required in government offices and that tools like Google Translate exist for daily life.

These commenters were far less gentle, calling nearly two decades without learning the local language a choice, not a failure. To them, continued dependence on a child was unreasonable and unfair.

This response focused on boundaries over confrontation. Help when available. Don’t cancel work or important plans.

This story lands right in the painful space between duty and burnout. Helping family shouldn’t mean sacrificing your own life indefinitely.

Was she wrong to draw a boundary now, or was this long overdue? At what point does “family helps” turn into quiet exploitation?

How would you redistribute responsibility in this situation? Share your thoughts below.