Holiday dinners are supposed to be warm, welcoming, and inclusive, but sometimes, even well-meaning families miss the mark.

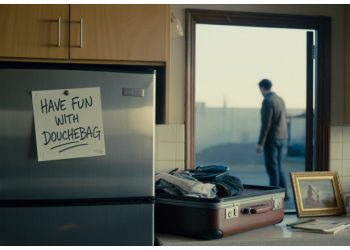

A visually impaired man in his early 20s recently shared why he left his family’s Christmas dinner early after struggling to eat due to poor lighting. While he isn’t fully blind, he explains that lighting, shadows, and contrast have a major impact on what he can see, sometimes more than his actual eye condition.

At the dinner table, the family was seated close together in a conservatory with yellow-toned overhead lights. The setup made it impossible for him to both see his food and reach it at the same time. When he leaned back, he could see but not eat. When he leaned forward, his head blocked the light and cast deep shadows over his plate.

Despite trying to explain this, his family seemed to misunderstand the issue. Some offered to add more food to his plate. Others commented on how good the meal was, as if he were criticizing it.

Feeling overwhelmed and unable to resolve the situation, he quietly left the table to calm down.

Now he’s wondering: did leaving make him the problem?

Now, read the full story:

What stands out here isn’t rudeness, it’s exhaustion.

Living with a “less visible” disability often means having to explain the same thing again and again, especially to people who think they already understand. The OP wasn’t refusing to eat. He wasn’t complaining about the food. He was stuck in an environment that literally prevented him from functioning.

And instead of adapting the environment, changing seats, adjusting lighting, or asking what would help, the responsibility was subtly shifted back onto him.

That’s a heavy burden, especially during an already overwhelming holiday setting.

Visual impairment exists on a wide spectrum, and one of the most misunderstood aspects is how environmental factors, lighting, glare, shadows, and contrast can dramatically affect functionality.

According to the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), many people who are severely sight impaired may still have usable vision, but that vision can fluctuate depending on surroundings. Poor lighting can make everyday tasks, including eating, extremely difficult or impossible.

Depth perception issues are also common in visual impairment. When shadows are present, objects can appear distorted, flat, or disappear entirely. For someone relying heavily on residual vision, this can make something as simple as locating food on a plate overwhelming.

Autistic individuals may experience additional sensory overload in these situations. Bright lights, crowded spaces, repeated questioning, and the pressure to “explain yourself correctly” can compound stress quickly.

Disability advocates emphasize that reasonable accommodations are not favors, they are necessities. Adjusting lighting, repositioning a chair, or allowing assistive tools like lamps or phone lights are simple, effective solutions.

Dr. Thomas Papadopoulos, a specialist in low-vision rehabilitation, notes that family members often unintentionally minimize challenges when a disability is familiar. Over time, visibility becomes invisibility, people assume adaptation has already happened.

That assumption is harmful.

The OP’s decision to leave wasn’t avoidance; it was self-regulation. Removing oneself from an overstimulating environment is a healthy coping strategy, not a failure.

From a social standpoint, there is no obligation for a disabled person to remain in a situation that causes distress simply to preserve appearances. Accessibility includes emotional safety as much as physical accommodation.

Importantly, the OP later clarified that his family did not see his departure as rude and apologized once the situation was discussed calmly. That outcome highlights something crucial: many conflicts around disability stem from misunderstanding, not malice.

But misunderstanding still has consequences.

The takeaway isn’t that families are uncaring, it’s that disabilities require active awareness, even after years of coexistence. Needs don’t disappear just because they’re familiar.

Here’s how the community responded:

The overwhelming consensus: Not the problem.

Many shared similar disability experiences.

A few misunderstood but were corrected.

This wasn’t about Christmas dinner but visibility, both literal and emotional.

The OP didn’t storm out. He didn’t accuse or blame. He recognized that the situation was overwhelming and removed himself to regulate. That’s not rude. That’s self-care.

Disabilities that aren’t always visible are often the hardest to advocate for, especially around people who assume they already “get it.” But accommodation isn’t a one-time lesson. It’s an ongoing conversation.

The good news? When the conversation finally happened, understanding followed. Apologies were made. No one took offense.

Sometimes, stepping away is what allows clarity to come later.

So what do you think? Should people with disabilities feel obligated to “push through” for the sake of politeness—or is leaving the healthiest option?