A routine school email turned into a full-blown parenting reality check.

One mom thought she had done everything right. Paperwork signed. Medication clearly labeled. Instructions followed. Her twin sons, both 11, responsibly taking allergy meds and eczema cream at school as needed.

Then the message landed in her inbox.

The school explained that her boys still look “too similar,” and the mix-ups have not decreased. Their solution was not better procedures or extra checks. Instead, they asked the parent to make the children “easy to distinguish” going forward.

That suggestion did not sit well.

The twins already wear identical uniforms. They are not identical twins, but close enough that adults still mix them up. And now the burden of safe medication administration seems to be shifting away from trained staff and onto the family.

The mom understands the safety concern. What she does not accept is the implication that it is her job to physically mark or modify her children so adults can do theirs.

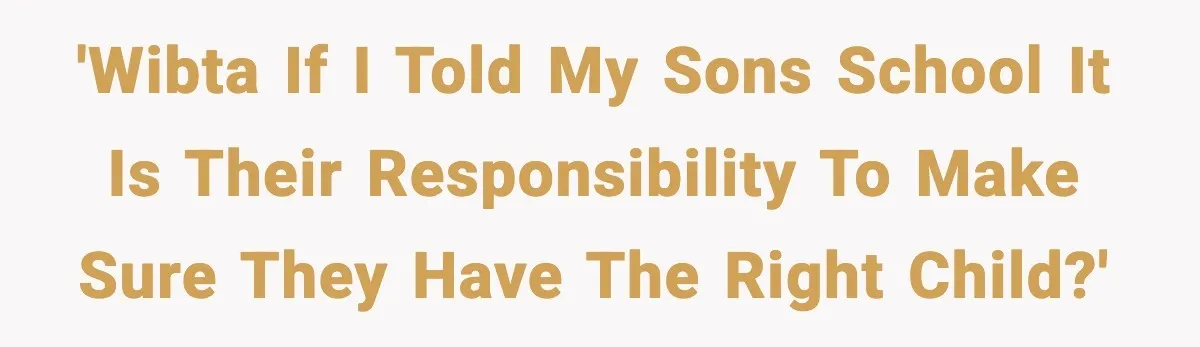

So she is considering telling the school exactly that.

Now, read the full story:

This request would stop most parents in their tracks.

The safety concern is valid. Medication errors matter. But the solution proposed here feels wildly misplaced. Asking a parent to visually mark children because adults cannot follow basic verification steps raises more questions than it solves.

What stands out is the age of the kids. These are not toddlers. They are capable of stating their names, their classes, and the medication they take. That is exactly why identity checks exist.

The discomfort comes from the implication. If the school cannot reliably identify students before administering medication, that problem runs far deeper than twins who look alike.

This kind of frustration is common when institutions quietly shift responsibility downward instead of fixing process gaps.

The core issue here is not the twins. It is procedure.

In healthcare and care-adjacent settings, identity verification sits at the center of medication safety. The NHS and similar bodies emphasize the “five rights” of medication administration, which include giving the right medication to the right person, every time.

Those checks exist precisely because people can look alike. Hair changes. Faces age. Uniforms match. Visual identification alone is never considered sufficient.

Training guidelines for medication administration in the UK stress that staff must confirm identity verbally whenever possible, especially when the individual can communicate clearly.

Experts agree that responsibility cannot be outsourced to appearance. According to patient safety guidance, relying on visual cues increases error risk rather than reducing it.

From a developmental standpoint, 11-year-olds are more than capable of participating in their own care. Pediatric health guidance encourages children of this age to name their medications and advocate for themselves under supervision.

The school’s concern about medication mix-ups is understandable. Their solution is not.

Actionable steps that actually reduce risk include:

- Asking the child to state their full name before medication.

- Checking that name against labeled medication and records.

- Confirming the medication type verbally with the child.

- Documenting administration consistently.

None of those require changing the child.

The deeper issue is accountability. When systems fail, the fix should strengthen the system, not shift liability to families.

The takeaway is simple. Safety protocols exist for moments exactly like this. Ignoring them creates far more risk than two children who happen to share a face shape.

Check out how the community responded:

Most Redditors backed the parent and pointed out the obvious solution, ask the child their name.

Others focused on professionalism and proper medication procedures.

Some reacted with disbelief at the request itself.

This situation feels absurd because it highlights a deeper issue.

The school identified a real risk, then reached for the wrong fix. Safety improves when procedures tighten, not when children are expected to become walking labels.

The parent’s instinct to push back makes sense. Medication administration requires care, attention, and verification. Those responsibilities sit squarely with the adults assigned to do the job.

Twins existing in the same space is not a flaw. It is a scenario systems should already be designed to handle.

So the question remains: Should parents accommodate institutional shortcuts, or insist that standards are followed? And if a school cannot reliably identify students for medication, what else might be slipping through the cracks?