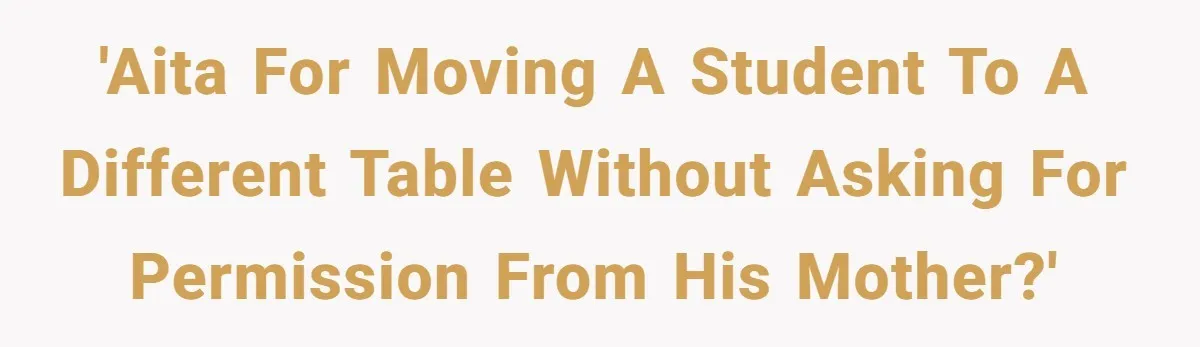

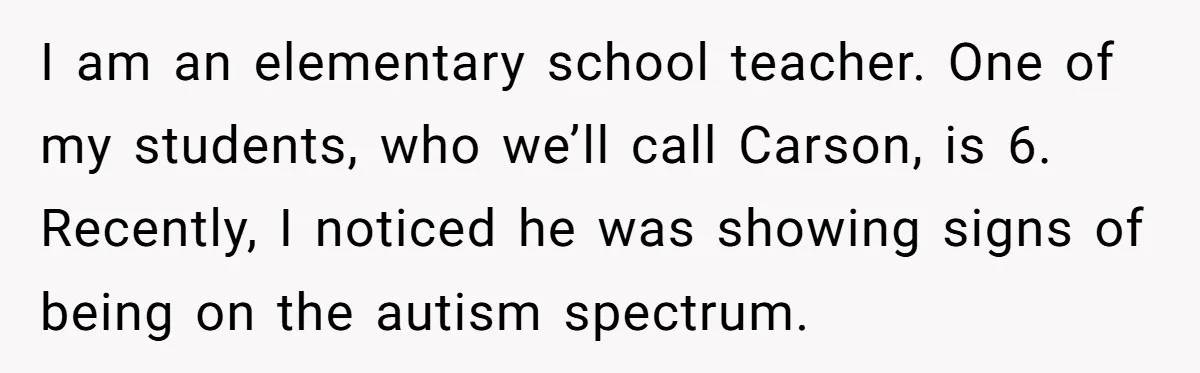

Some classroom problems begin quietly, the kind you notice only when you are the one standing in front of twenty small kids every day. That was the case for an elementary teacher who started seeing signs that one of her students, a gentle six year old boy named Carson, was struggling in ways his classmates were not.

He avoided eye contact. He flapped his hands when he became overwhelmed. Loud noises made him shut down. And the fluorescent lights in the room, the kind most adults barely register, seemed to unsettle him the most.

The teacher had been through this before with other students. She knew what sensory overload looked like. She also knew how quickly kids could turn on someone who seemed different. When a few students started teasing Carson, she stepped in and tried to make sense of what he needed to feel safe.

But when she brought her concerns to his mother, everything took a complicated turn.

Here is how the story unfolded.

During their parent teacher conference, the teacher gently explained what she had observed. She mentioned sensory challenges and possible accommodations that could make Carson’s school day easier. Instead of relief or curiosity, she was met with a wall of defensiveness.

His mother snapped that Carson was perfectly normal. She insisted he was nothing like his older brother Trevor, a nine year old in a specialized program because he is nonverbal and autistic.

The conversation shut down so quickly that the teacher left feeling discouraged. She wanted to support this child, but she also understood she had reached the limit of what the mother was willing to hear.

Back in the classroom, the signs continued. The fluorescent lights made Carson blink rapidly and lose focus. He fidgeted, flapped his hands, and sometimes looked on the verge of tears.

The teacher knew she had to do something. She moved him to a table tucked into a quieter corner of the room. Overhead lights stayed off above that spot, and she placed a small lamp on the table instead. It was a simple change that cost nothing.

Almost overnight, Carson transformed. He was calmer, happier, and fully engaged. He finished assignments with confidence. He smiled more. The teasing from other students faded because he no longer reacted in distress. The teacher felt hopeful for the first time in weeks.

That hope did not last long. When Carson’s mother found out about the seating change, she fired off an angry email demanding that he be moved back immediately. She accused the teacher of singling him out.

She insisted that nothing was wrong with him and claimed the teacher should have asked permission before adjusting his environment. The teacher tried to explain that the new space helped him focus, but the mother refused to believe any of it.

Now the teacher was stuck between a student who was finally thriving and a parent who saw accommodation as an insult rather than support.

Psychology and Motivation

The heart of this conflict lies in denial. Parents often struggle when one child receives a diagnosis, especially one as misunderstood as autism. Sometimes that denial becomes even more rigid when a second child shows signs of similar needs.

The mother might fear that labeling Carson would limit him. She might carry guilt or exhaustion from navigating his brother’s challenges. Recognizing another child on the spectrum could feel like a loss she is not emotionally ready to face.

For the teacher, the motivation was simple. A student was struggling, and she had the tools to help. Teachers adjust seating every day for behavior, attention, sensory needs, or peer conflict.

It is an ordinary part of classroom management. Waiting for parental approval for every small adjustment would make the job impossible.

Still, even well intentioned decisions can run into emotional landmines when parents feel out of control.

Reflection

This situation carries a familiar tension that many educators recognize. Teachers are often the first people to notice early signs of neurodivergence.

Parents, however, are the ones living with the fears, hopes, and complicated feelings that come with it. When those worlds collide, the child ends up in the middle.

Could the teacher have phrased things more gently? Maybe. But nothing suggests the mother was ready to hear it in any form.

And a student’s well being cannot wait for perfect timing. In the end, the teacher’s quiet intervention gave Carson what he needed. It is hard to call that anything but the right thing to do.

Here’s what people had to say to OP:

Many praised her empathy and her effort to create a space where Carson could focus without sensory distress.

Several pointed out that it is the teacher’s job to arrange seating as needed, not the parent’s.

Others shared their own stories, describing migraines triggered by fluorescent lights or childhood experiences where teachers ignored early signs of autism.

Sometimes the smallest changes make the biggest difference in a child’s life. A lamp in a quiet corner can be the difference between a child falling behind and a child discovering the joy of learning. The mother may not be ready to acknowledge what is happening, but the teacher has already done what good teachers do. She saw a child in distress and met him where he was.

What do you think? Was the teacher right to act or should she have waited for a permission she was unlikely to get?