Claudia Cardinale, admired for her beauty, was once called Italy’s best invention after spaghetti by her co-star David Niven. She shared that she turned down several famous admirers over the years, adding, “They tried. I turned down seducers.” Her mischievous laughter showed she enjoyed recalling these moments.

At 84, Cardinale was in Rome for the Italian premiere of a restored version of the 1963 film La ragazza di Bube (Bebo’s Girl), in which she won the Nastro d’Argento award for best actress. The film is about a girl who stays loyal to her man, even after he’s sent to jail.

This film will be featured at the Museum of Modern Art in New York as part of a 23-film tribute to Cardinale, running until February 21. It’s a rare honor, as MoMA has only occasionally celebrated living actors in its history.

Joshua Siegel, a MoMA curator, said in a video message at the Rome screening, “Beautiful actresses come and go, but they usually don’t last for 60 or 65 years.”

Cardinale won’t be going to New York for the film retrospective; she finds traveling tiring now and uses a cane. She prefers to stay out of the spotlight.

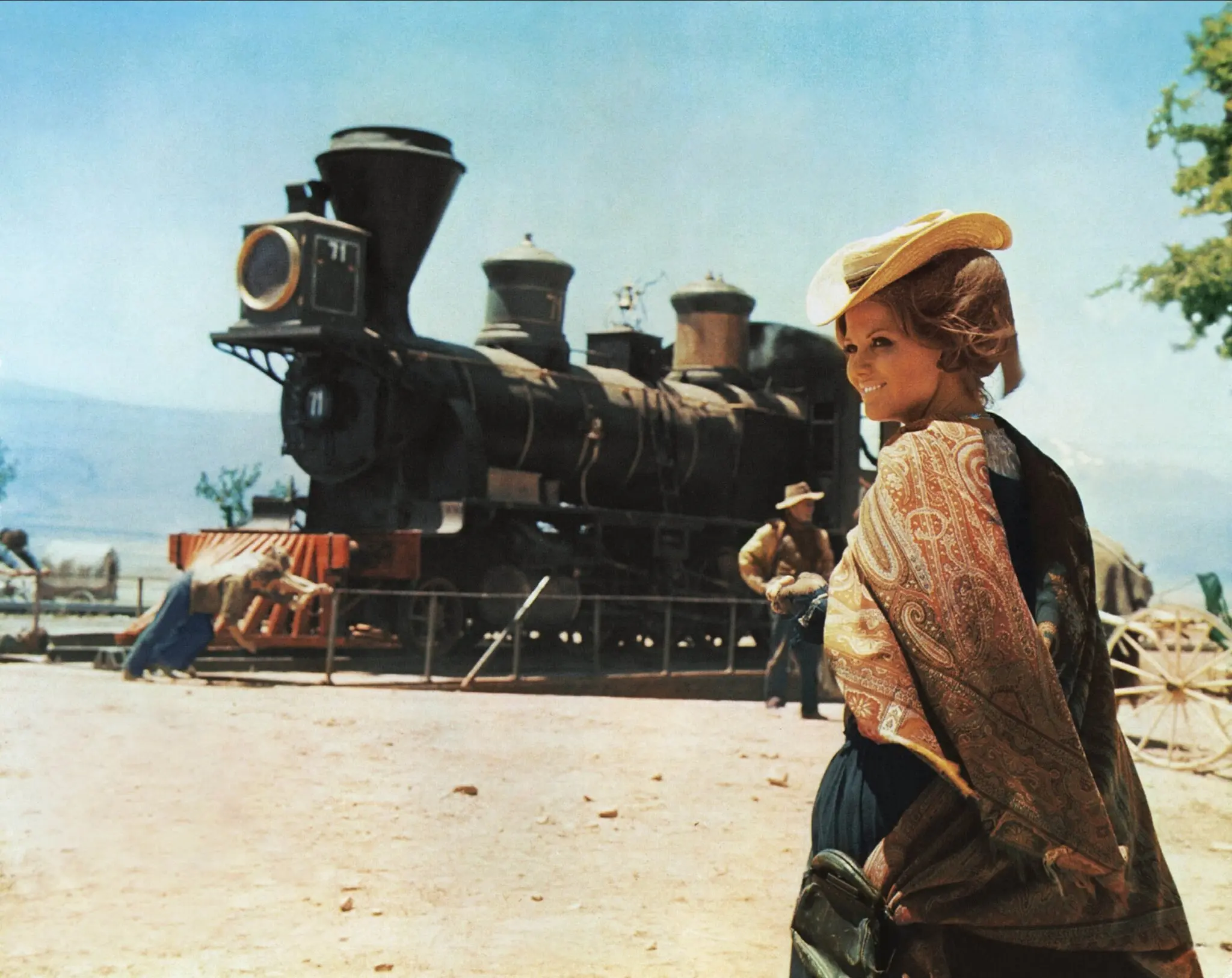

Cardinale has been in the public eye for a long time, acting in over 100 films since 1956. She’s especially known for her roles in classic Italian movies: as Ginetta in Rocco and His Brothers; as Angelica in The Leopard; as Claudia in 8 ½; and as Jill in Once Upon a Time in the West.

She also starred in Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, a famously challenging film shot in the Peruvian jungle.

Cardinale called Fitzcarraldo “the adventure of my life,” but when asked about her favorite roles, she said, “My God, I’ve done so many, I don’t know which one I prefer.” She added with a laugh, “Maybe Once Upon a Time in the West, and then so many others.”

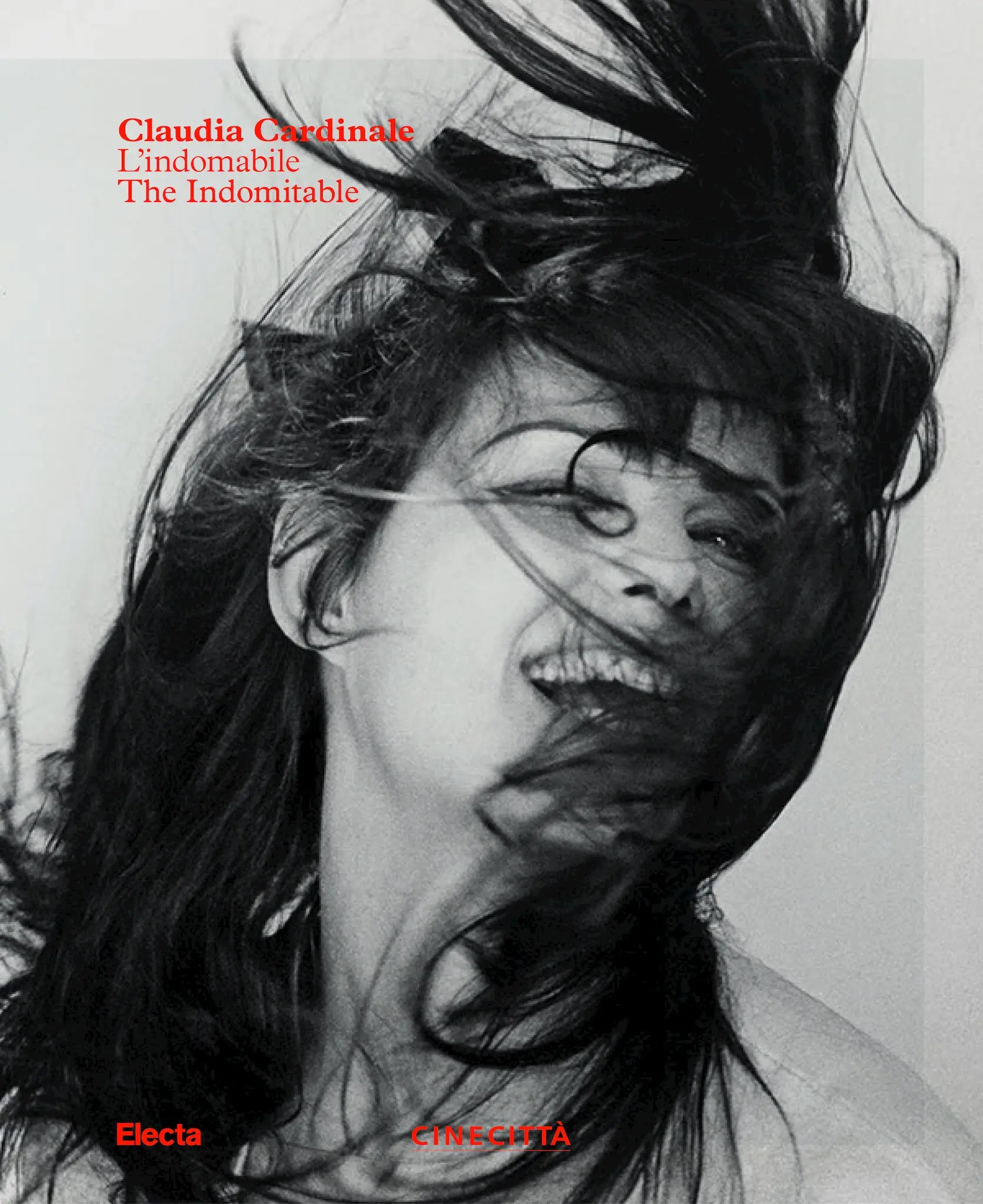

The MoMA tribute, organized with Cinecittà, includes some of Claudia Cardinale’s most famous films.

But it also features three lesser-known works that might not be familiar to American audiences: Bebo’s Girl, Marco Ferreri’s 1972 film The Audience, about a man obsessed with meeting the pope, and Pasquale Squitieri’s 1990 film Atto di Dolore, about a widow struggling with her son’s drug addiction.

Even though Cardinale is now a huge name in Italian cinema, she spoke very little Italian when she arrived in Italy in 1957.

Born in Tunisia in 1938 to Sicilian immigrant parents, Cardinale still feels a connection to her birthplace. At a ceremony in May, where a street was named after her in La Goulette, near Tunis, she shared, “I still feel a little bit Tunisian.”

Her big break came in 1957 when she won the Most Beautiful Italian in Tunisia contest. The prize was a trip to the Venice Film Festival, which marked the beginning of her acting career.

In the book Claudia Cardinale: The Indomitable, published by Cinecittà and Electa for the MoMA tribute, critic Masolino D’Amico recalls seeing Cardinale for the first time at the Venice Film Festival. He describes her as “splendid in all her youthfulness,” wearing an emerald green bikini and happily posing for the paparazzi.

D’Amico notes that she seemed to treat the flurry of camera clicks like a game. “She was not — I understand this clearly now — trying to be sexy, and maybe not even attractive. She was simply happy to be there,” he writes.

At the festival, Cardinale attracted the attention of Franco Cristaldi, one of Italy’s leading producers at the time. Cristaldi, like Pygmalion, helped turn the young actress into a star and became her life partner.

He also adopted her son, Patrick Cristaldi. Initially, Patrick was introduced as her brother to preserve Cardinale’s “virginal feel and glow,” according to Cardinale’s daughter, Claudia Squitieri.

However, stardom came with its challenges. Cristaldi’s contract in 1962 controlled every aspect of Cardinale’s life, both professional and personal. She accepted the terms reluctantly because she needed to support her family and raise her child.

Cardinale’s life changed dramatically in 1973 when she met director Pasquale Squitieri on the set of I guappi (“Blood Brothers”). The two fell deeply in love, which affected their careers. Cristaldi’s influence in the Italian film industry was significant, and crossing him was risky.

Claudia Cardinale worked on nine films with Pasquale Squitieri, even after she moved to Paris and he stayed in Rome. Though they never married and eventually parted ways, they remained close.

Now, Cardinale lives near Fontainebleau, France, with her children, Claudia Squitieri and Patrick Cristaldi. She has established a foundation that supports women’s rights and environmental causes. Since 2000, Cardinale has been a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador, working to improve the status of women and girls.

She is also the honorary president of Green Cross Italy, an organization that promotes environmental sustainability and sponsors a film award at the Venice Film Festival. Claudia Squitieri manages the foundation and views it as a way to continue her mother’s legacy.

Cardinale has spoken fondly of her daughter, saying, “I am lucky to have this daughter, who I adore. She looks after me; she looks after everything.”

Since Cardinale won’t be in New York for the retrospective, Squitieri will represent her. The screening of Bebo’s Girl on Friday will be followed by a whimsical short film titled Un Cardinale donna (“A Woman Cardinal”), produced by Manuel Maria Perrone for the retrospective.

At the film’s Rome premiere, Perrone described working with an icon like Cardinale as both challenging and delicate. “She’s been doing this her whole life,” he said. “Being an icon is her job.”