Sometimes the smallest acts of pettiness feel like a warm bath for an old wound.

This is one of those stories. Picture a group of teenagers nursing breakup wounds, seething about the unfairness of being dumped and looking for a way to reclaim a sliver of dignity and satisfaction.

Your friend’s boyfriend was a dishwasher at a local restaurant. He had one specific gripe about his job, scrubbing lipstick rings off glasses. He said it like it was the bane of his existence.

A human can only take so much. And when he broke up with your friend in a lousy way, that gripe became a target.

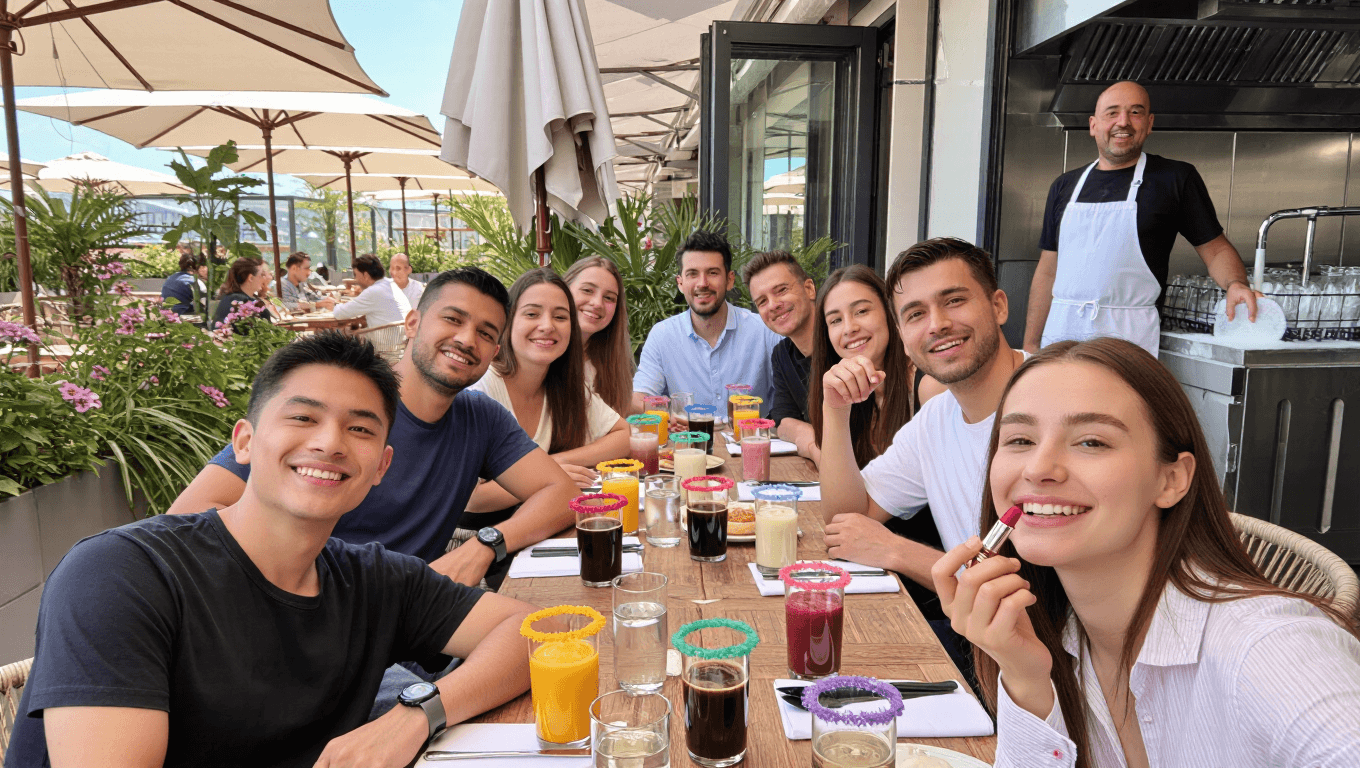

So on a Saturday morning, when he was scheduled to be working, you all showed up for brunch. You ordered smoothies, juices, coffee, water, every drink you could think of that came in a glass.

Every time, you applied a fresh layer of lipstick before sipping. The result was ritualistic cleaning hell for one unsuspecting dishwasher.

It was petty. It was small. It was completely legal. And it felt good.

Now, read the full story:

It’s immediate how empowering small acts of shared mischief can feel when you’re young and wounded. Revenge rarely needs to be dramatic. Sometimes, it simply needs to sting in a way that makes your brain register, this feels like justice.

There’s a craftsmanship to this kind of petty payoff. It doesn’t harm anybody seriously, it doesn’t break laws, and it doesn’t require escalations. It just plays on someone’s specific irritation and amplifies it persistently.

That combination, specificity and persistence, is what makes the memory so vivid. Years later, you can still recall the image of that dishwasher scrubbing glass after glass. The act captures more than simple retaliation. It captures camaraderie, shared perspective, and the way small, creative action can help someone reclaim a sense of agency after emotional hurt.

But why do these little revenge stories feel so satisfying? To unpack that, let’s look at the psychology of petty payback and what experts say about it.

This story sits squarely in the realm of petty revenge, small, targeted actions meant to symbolically right a perceived wrong.

Psychologists have long studied revenge not as violence, but as a social emotion that serves particular psychological functions. In a 2013 study in Social Psychological and Personality Science, researchers found that people often pursue revenge not for material gain but for emotional equilibrium.

When someone feels wronged, especially in intimate relationships, the desire for a response that feels fair can linger. It’s not about hurting the other person badly; it’s about restoring a sense of control and balance.

That’s where petty revenge shines.

Symbolic retaliation differs from aggressive or harmful revenge in several key ways. It is:

-

Proportionate: A response tied to a specific irritation rather than a general desire to harm.

-

Creative: Humor and ingenuity play a role.

-

Non-violent: It avoids physical harm or risk.

-

Ritualistic: It creates a shared story that reinforces group bonds.

In the OP’s story, the targeted annoyance — lipstick on glasses — wasn’t random. It was an irritation the dishwasher regularly complained about. That specificity gave the action meaning.

Psychologist Dr. Peter Coleman, a conflict resolution expert, explains that revenge often stems from the need to signal that a boundary was crossed.

In this situation, the breakup was a boundary violation for the friend group. Instead of confrontation, the group chose a playful form of signaling: they amplified the dishwasher’s own complaint back at him.

That upward amplification, using the other person’s own words as a tool of retaliation, is a key mechanism in petty payback. It satisfies without escalation.

The 2018 Emotion journal study on revenge emotions highlights that acts of symbolic retaliation can boost feelings of satisfaction and closure, even when nothing is “fixed” in a practical sense.

That doesn’t make petty revenge noble. But it does help explain why people reminisce about it years later with a chuckle.

In the context of a breakup, this kind of payback can:

-

Strengthen alliances within a friend group

-

Serve as a stress release

-

Offer a sense of justice without violence

-

Create a story that transforms hurt into humor

This differs from ongoing cycles of retaliation. When revenge becomes habitual or escalatory, it can lead to real conflict. But short, one-off, proportionate actions rarely do.

Experts caution that revenge can become harmful when it targets a person’s dignity, livelihood, or safety. A 2014 review in Personality and Social Psychology Review found that when retaliation becomes personal or dehumanizing, it can stoke long-term conflict.

The OP’s story avoids this. It targeted a complaint, not a person’s core worth. A waiter scrubbing glasses is a job task, not an identity. That matters.

Still, any action taken in the name of “getting even” benefits from thoughtful reflection. Humor can unite, but targeting people directly can divide. The key difference is intent and impact. This story kept impact light.

Petty revenge occupies a unique spot in human emotion. It is not about violence or destruction. It’s about narrative, psychology, and reclaiming a sense of hurt with wit instead of anger.

This brunch gag worked not because it was cruel, but because it was clever, and because it gave a hurt friend a moment of control when she had felt powerless.

Check out how the community responded:

Readers celebrated the cleverness and harmless nature of the petty revenge.

Others highlighted the supportive friendship dynamic behind it.

This story reminds us that not all revenge needs to be dramatic or destructive. Some acts of payback are rooted in creativity, shared experience, and the simple desire to help a friend feel seen and validated.

The lipstick stunt did not ruin anyone’s life. It created a moment of satisfaction, laughter, and bonding that helped a friend move past a hurtful breakup. That’s the kind of human response that can transform lingering resentment into shared memory.

Petty revenge like this occupies a special place in our social imagination because it delivers justice in miniature. It does not escalate harm. It does not endanger anyone. It simply lets someone feel a little understood and a little victorious.

So what do you think? Is this the ideal form of petty revenge, harmless but pointed? Or do you think even small acts of one-upmanship risk prolonging emotional wounds?