She did not walk away because of distance. She walked away because of fear.

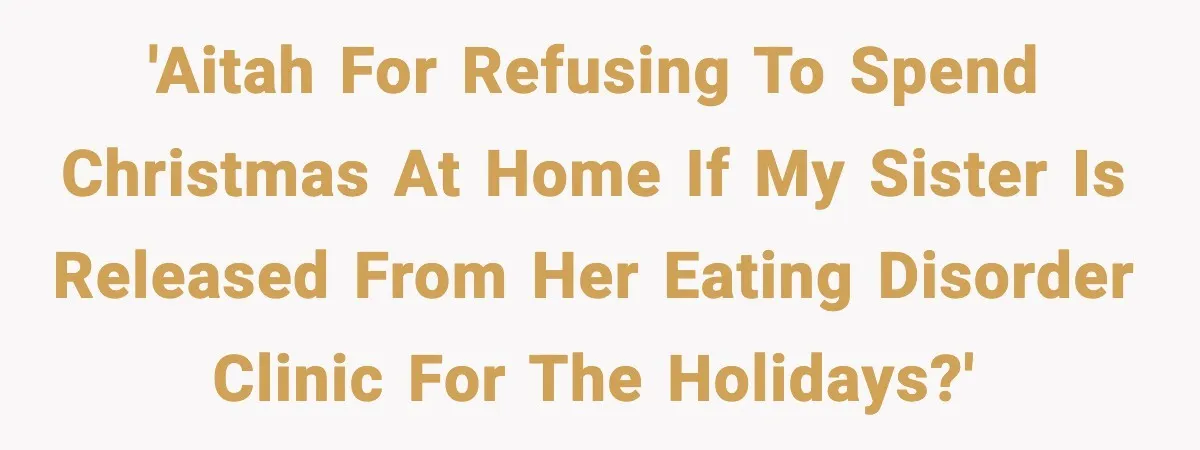

For one Redditor, this holiday season was supposed to bring warmth, laughter, and tradition. Instead, it forced a choice between emotional safety and family expectations. Her sister, now 18, has struggled with an eating disorder for years.

What began as illness became something darker. It spilled into personal attacks, cruel insults, and explicit wishes for OP’s death.

At one point, her sister’s rage got so bad that adults had to physically remove her from the house.

Now, after months in inpatient treatment, her sister might come home for Christmas. Her parents believe family togetherness will aid recovery. Her extended maternal family says she deserves reinforcement and support.

But the memories of emotional violence cut deep. OP does not want to spend the holiday in the same house as someone who once threatened her life. Her paternal grandparents offer refuge. Her parents say she must stay home because she is a minor. So she plans to leave through a backdoor they cannot block.

This is not petty family drama. It is a boundary born of fear.

Now, read the full story:

This is not simple holiday conflict or teenage stubbornness. This is deep fear layered over repeated emotional harm.

OP’s sister’s illness is real, and deserves support. But what also matters are boundaries that protect safety and dignity.

When someone’s words or behavior repeatedly threaten your sense of security, it’s not unreasonable to step away. And her parents’ insistence on unity without addressing the harm reshapes the issue into something bigger.

It becomes about whose comfort matters more. This kind of emotional injury doesn’t disappear because of a calendar date. This feeling of imbalance and fear is deeply human, especially for someone who feels unseen and unheard by their parents for long stretches of life.

It’s worth looking at what research says about situations like this.

At the heart of this story is family dynamics strained by chronic illness, harmful communication, and boundary violations. Eating disorders are complex medical and psychological conditions. They affect not only the person diagnosed but also the family system.

Research shows that living with or caring for someone with an eating disorder can create intense emotional conflict, blurred roles, and psychological stress for siblings and parents alike. But when supportive responses collapse into pressure for reunion, distress continues.

Family estrangement is not an isolated pattern. A growing body of research shows that estrangement is more than conflict or momentary anger. Estrangement often results when one member feels that reconciliation is impossible or undesirable for their well-being.

This does not make the choice easy. It does make it personal and sometimes necessary.

One psychologist who studies family estrangement notes that the process often involves complicated layers of trust, values, behavior, and meaning. This reinforces that estrangement is not merely about refusal to talk. It’s about protecting psychological and emotional safety in the face of repeated harm.

Research also highlights the impact of childhood emotional neglect and unhealthy family environments on adolescents’ trust and emotional regulation. Emotional neglect during childhood is linked to feelings of isolation, exclusion, and detachment from parents.

Although OP’s situation includes abuse as well as neglect, both pathways show how harmful family dynamics can lead young people to disconnect as a survival strategy.

Experts emphasize that establishing and maintaining safe boundaries can be a healthy response when relationships consistently undermine emotional security. Dr Burgess, who has written on family estrangement, advises that setting limits and prioritizing self-care are crucial when dealing with difficult family members and unresolved conflict. This approach includes taking time to process grief, protect your emotional space, and let healing happen at your own pace.

When families push for forced reunion, they often overlook the harm that led to division. In clinical settings, counselors frequently help families unpack deep wounds before they ever consider holiday gatherings. Simply insisting that everyone “pull together” without addressing past harmful behavior is unlikely to generate true healing.

Instead, experts suggest acknowledging the hurt, validating each person’s experience, and building a conversation around respect rather than obligation. That does not require a holiday dinner. Another important aspect involves the developmental and power imbalance.

At 16, OP is legally a minor and still under parental authority. But authority does not override safety. Therapists and child advocates often recognize that visible fear of another’s behavior is a serious concern, not a trivial complaint. This aligns with guidance that boundaries are not punishment, but protective measures that allow space for emotional recovery and healing.

Taking a holiday away from a threatening environment is a concrete example of that.

So how do families navigate this? Experts encourage open dialogue with professional support.

Family therapy, especially with clinicians trained in eating disorders and trauma, can help parents and siblings understand each other without forcing proximity.

Sometimes, separate celebrations are the safest route. Sometimes, after prolonged healing and accountability, relationships shift. But healing rarely happens overnight, and it rarely happens because of a date on the calendar.

The core message here is nuanced. Protecting your emotional and physical safety is not selfish. It is survival. And when past patterns include threats and fear, choosing peace does not make you wrong. It makes you mindful.

Check out how the community responded:

Most commenters strongly supported OP’s decision and recognized the seriousness of the threat. They encouraged prioritizing safety in a situation that clearly harmed her.

Another group focused on the dangerous behaviour and urged formal protections. They emphasized that eating disorders do not justify threats against others.

A smaller set spoke to the treatment’s effectiveness and long-term environment. They questioned whether the clinic was helping and whether emotions would improve.

This story shows how complicated love and safety can be in one family. OP’s sister is sick. That makes her painful to be around.

But the pain did not stop with her illness. It spilled over into explicit threats and fear-inducing behavior. Her parents’ hope that Christmas would help her heal is understandable. But hope without accountability and boundaries can feel like pressure, not support.

OP’s decision to spend Christmas with her grandparents is not a rejection of her sister’s illness. It is a choice for her own safety and emotional well-being.

Boundaries sometimes look like distance. They allow space for healing without demanding immediate reunion. But boundaries should also come with honest conversations, therapeutic support, and empathy on all sides.

So what do you think? Should families postpone holiday reunions when emotions are still volatile? Or is Christmas one of those moments where love must conquer fear? Would you prioritize safety or tradition if you were in OP’s shoes?